This article is co-authored by Marzia Lanfranchi of Cotton Diaries and feminist writer and narrative investigator Virginia Vigliar and has first been published on www.denimdudes.co - many thanks to Amy Leverton for putting it up there and thanks to all of you for making this accessible to us!

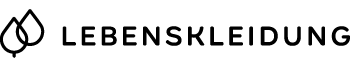

"Britain, at the time the most powerful nation in the world, relied on slave-produced American cotton for over 80 percent of its essential industrial raw material." not considering the millions of people involved in the cotton textile industry, historian Gene Dattell explains.

Free Cotton

Women’s role

The women of the revolution

Revolution and change happen on multiple levels, but a sad truth is that often those who work for change behind the limelight remain unknown. It is a historical trend that women have remained invisible and often not recognized for their merits. The fact that we celebrate Women History month in March is a clear indicator of who has been left out of the history text books.

For example, much has been written about Clarks' shoes and the shoemaking pioneer founder, James Clark, whilst the anti-slavery work of his Quaker wife, still goes unrecognised.

Though her anti-slavery efforts and campaigning for free cotton spanned across various activities, her most notable contribution to the Free Cotton movement was probably the ‘Free Labour Cotton Depot’ she founded with her husband. "Between 1853 and 1858 the ‘Street Depot’ sold a highly specialised range of cotton goods, chiefly cotton cloth by the yard. The goods were verified as ‘free labour,’ and made from cotton grown by waged, or ‘free’ labour, rather than slave labour." reports A. P. Vaughan Kett.

She also leveraged her tight network of Quakers women across the Atlantic and established a female philanthropic sewing society called ‘The Olive Leaf Society,’ that raised funds for the Connecticut peace and anti-slavery (male) campaigner, Elihu Burritt. In 1861, Eleanor wrote "Cotton," (under the pen name “Eva,” which was a reference to Uncle Tom’s Cabin) the essay where she critiqued the institution of slavery, discussed the matter of free or waged labour, but also the concerns over the American crisis, the risk of slave-labour in other countries and the opportunities to build a slave-free supply chain in West Africa.

Whilst there was awareness about slave-produced sugar, the fact that American cotton was not produced by free labour was still not widely discussed in the UK.

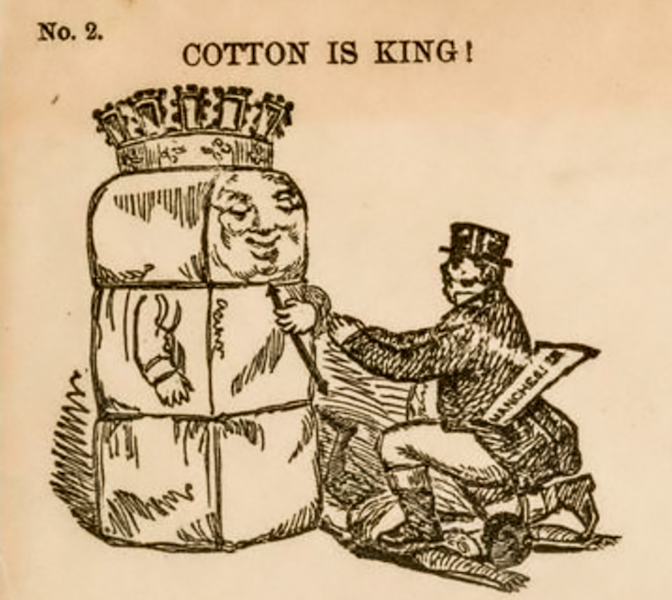

Sarah Redmond, a free African American lecturer, came to the UK to raise awareness and campaign against slavery. In 1859 she gave a lecture, calling on women in particular to raise public opinion and support the work of the American abolitionists. She reminded them of the terrible abuses suffered by female slaves, and that Manchester’s own prosperity was based on slave-grown cotton.

‘We have states where, I am ashamed to say, men and women are reared, like cattle, for the market. When I walk through the streets of Manchester and meet load after load of cotton, I think of those 8,000 cotton plantations on which was grown the 125 millions of dollars’ worth of cotton which supply your market, and I remember that not one cent of that money ever reached the hands of the labourers.’

Considerable public awareness of free cotton was also raised by abolitionist Harriet Beecher Stowe, author of "Uncle Tom’s Cabin," one of the most influential antislavery books, said to have "helped lay the groundwork for the Civil War", recruited many women, who looked to Stowe for leadership in the anti-slavery movement.

These are just a few mentions to the women who gave considerable contribution to the movement, although influential, many others remain unknown. Precisely, what these women ultimately wanted to do was show consumers how their choices were having a direct impact on human rights violations. Is this sounding familiar yet?

What are we now?

Whether it is because of their compassionate nature or empathy, women are still today at the forefront of sustainable fashion. Women and clothing are still intricately linked in a web of inequality and misrepresentation.

Some people may believe that slavery is in the past, a crime that was fought against and laws eventually abolished. But slavery still exists today – as the Guardian stated “there are more people trapped in modern slavery than ever before in history. 40.3 million people are living in modern slavery – more than three times the figure during the transatlantic slave trade” and 71 percent of these are women.

Garment production is one of the most female-dominated industries in the world. We know that the majority of these females are low-paid, informal workers in developing countries where gender discrimination is deeply-rooted in the system. As a result, women working in the garment industry are more vulnerable than men to conditions of modern slavery, driven by the race to the bottom of unethical brands.

On the other side, is the fact that despite the majority of fashion being aimed at female consumers, most CEOs of big fashion brands are male. It is the women who are, instead, leading in the sustainability fight although we see signs of change in my day-to-day work, I still experience a big gap between the work that so many women put in bringing forward the sustainability discourse, and the representation and decision-making role that these women eventually play in the industry.

In the cotton industry, the disparity between men and women’s attendance is alarming. For example, recently I attended in the same week a leading sustainability conference and a high-level cotton conference. With the events so close to each other I was able to notice that the cotton industry still has a long way to go in terms of female representation (which I would say was as low as 10%) whereas the sustainability world has more representation but less women in positions of power.

Undoubtedly, there is still work to do. Sustainable fashion history teaches us that a gender conscious approach is key in moving forward. All brands must recognise the role that all women play and have played until now to fight for a fair and just fashion industry.

Referenzen: